In This Issue

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, viewpoints or official policies of Autism Society Alberta.

|

|

|

End article-->

Autism Society Alberta's 2021

Virtual Annual General Meeting and Resource Fair

We hope you join us on Thursday, October 14th at 4 pm MDT for a short Annual General Meeting and informative Resource Fair.

Resource Fair!

Presentations will cover topics including Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD) Navigation, a Parent Panel on Persons with Developmental Disabilities (PDD), Respite Care, and Financial Tips on Running your own Family Managed Service Programs. Presentations will cover topics including Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD) Navigation, a Parent Panel on Persons with Developmental Disabilities (PDD), Respite Care, and Financial Tips on Running your own Family Managed Service Programs.

Stay tuned for full details.

Registration is now open – Click here to register!

|

|

|

End article-->

Update on Rapid Testing, PPE, and Interim PDD/FSCD Policies

- PPE for your respite workers and other Family Managed Services staff can still be requested from your caseworker.

Information on Alberta’s Rapid Testing Program is available at https://www.alberta.ca/rapid-testing-program.aspx. Family Managed Services (FMS) Administrators under the PDD program and families accessing the Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD) program qualify for this under the same terms and conditions as a company. Disability Services is working with Alberta Health to get more information about the Rapid Testing Program, details pending. Information on Alberta’s Rapid Testing Program is available at https://www.alberta.ca/rapid-testing-program.aspx. Family Managed Services (FMS) Administrators under the PDD program and families accessing the Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD) program qualify for this under the same terms and conditions as a company. Disability Services is working with Alberta Health to get more information about the Rapid Testing Program, details pending.- Interim policies for FSCD and PDD remain in effect:

|

|

|

End article-->

Encouraging Communication – Tips, Tricks and Strategies

Kitty Parlby

Do you have an autistic family member, student or client who is non-verbal or only says a few words? I went through that for many years with my own son, Eric, as well as through my work as a one-on-one Educational Assistant. Throughout that time, I learned many methods of encouraging communication, and will share some of them with you.

First, whenever possible, try to communicate face-to-face. Remember that communication includes facial expression and body language. When Eric was very young I decided to become very expressive with these methods. If I was surprised, I might let that expression stay on my face a bit longer than usual, and then add a couple of words to go with it. My body language also lingered longer and had a lot of variety. When eye contact seldom happens, you get creative at stimulating attention, without saying “look at my eyes.” I did not hide my sad emotions, either. When I cried, Eric would touch the tears on my face and look in my eyes. All of this required great openness on my part, but it was the first step in modelling communication for my son.

Speaking of modelling, that is one of the key strategies I stress when teaching about communication. When Eric was non-verbal, I became a regular commenter on many things I saw, heard, and thought when we were out and at home. In this way I was feeding him vocabulary and expression ideas (including intonation, volume choices, etc.). At the same time, this was drawing his attention to the world around him. There is also “parallel talk”, where you narrate what they are doing, seeing, hearing or feeling. For example, if they are patting Rover, you might say “Patting the dog.” Speaking of modelling, that is one of the key strategies I stress when teaching about communication. When Eric was non-verbal, I became a regular commenter on many things I saw, heard, and thought when we were out and at home. In this way I was feeding him vocabulary and expression ideas (including intonation, volume choices, etc.). At the same time, this was drawing his attention to the world around him. There is also “parallel talk”, where you narrate what they are doing, seeing, hearing or feeling. For example, if they are patting Rover, you might say “Patting the dog.”

Having said that, there are times that it’s preferable to wait before you speak, which is a skill in itself when encouraging communication. It can take some practice, as most of us are used to almost instant response when we’re speaking with someone. However, when we wait it provides a more realistic window of opportunity for an autistic individual (or others with language challenges) to process what we said, think about what they want to express, mentally choose the words to accomplish that, and then physically get the words out of their mouth. So even if you have to count the seconds off in your head to delay yourself from asking again or speaking for them, this is an important element of encouraging reciprocal conversation. Try to wait for 15 seconds.

Remember that a little frustration can be a motivator to communicate. You don’t want enough frustration to cause distress, but like any of us, not getting what we want can lead us to pursue new skills to get it. Here are some other tricks and tips that may promote attention and verbalization:

- Voice modulation: speak loudly, then whisper; talk in a high, squeaky voice, then go low; speak like a robot, or use a sing-song voice. These methods might increase attention by increasing interest and fun!

- Follow their lead. Play along or mimic their actions. Their greatest interests (sometimes negatively thought of as obsessions) are your greatest motivation tool.

- Give choices. Hold up two items to choose from, or present the choices verbally, depending on their communication level. Choices also engender a feeling of having some control.

- Put their favourite items in less accessible places, perhaps a bit out of reach, so that they’ll need to use some form of communication to indicate what they want.

- Delay your reply, or pause in the middle of a sentence. If Eric said “Cookie,” I might look thoughtful and scratch my head, as though deciding. This would often get him to look up at me, and maybe speak again. Or I might say “I’m thinking that for supper I will make …,” and then pause. This too would have him looking at my face, and later on in his language development, he would even interject his suggestion: “Pasta!”

- Store preferred objects or snacks in containers that they need assistance to open, to encourage words like help, open, more, or please.

- Song and movement! It’s a fun, less invasive way to encourage shared communication, teach vocabulary with repeated phrases, and express feelings.

- Expand on their language. If they point and say “Bird,” you might say “I see a blue bird.” Even if they are just using gestures, you can add a word or two.

Using many of these strategies will hopefully discourage the temptation to ask questions all the time as a method to elicit speech, which can become tiresome very quickly. Last, but definitely not least, I use a lot of humour, smiles and laughter. I’ve always loved what I do in the autism community and the children that I’ve worked with, and conveying that feeling is the most important communication of all. Using many of these strategies will hopefully discourage the temptation to ask questions all the time as a method to elicit speech, which can become tiresome very quickly. Last, but definitely not least, I use a lot of humour, smiles and laughter. I’ve always loved what I do in the autism community and the children that I’ve worked with, and conveying that feeling is the most important communication of all.

Kitty Parlby is the mother of an autistic young adult. She is a former special needs Educational Assistant and an autism speaker and consultant with Autism Inspirations. She currently works as a Family Resource Coordinator for Autism Society Alberta.

|

|

|

Latest News from Autism RMWB

Summer is here and gone, just like that! We had the most amazing summer here at the Autism Society of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. During the months of July and August, we hit the highest attendance yet in our programs! Summer is here and gone, just like that! We had the most amazing summer here at the Autism Society of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. During the months of July and August, we hit the highest attendance yet in our programs!

Summer Camp ran from July 5th to August 13th. Over this period, we had 70 children aged 4-17 attend our camp! Groups of 12 kids each came for one full week, and we were able to attend many different activities during this time, including a boat ride on the river, play parks, Total Ninja Warrior, swimming, mini-golf, Vista Ridge, visits from the RMCP and many different therapy animals, and MUCH more. The kids (and staff) loved every single minute of camp, and the smiles on the children’s faces said it all.

Social Respite ran every day of the summer alongside summer camp, so the  kids could enjoy similar activities in respite and in camp. A record high number of hours were hit during July and August – over 1200 hours servicing 62 families! This is huge for us – this shows that all our hard work has been totally worth every minute. During social respite, children were able to attend swimming, Total Ninja Warrior, Vista ridge, golf lessons, Nature Walks, visits to the playpark, and much more. kids could enjoy similar activities in respite and in camp. A record high number of hours were hit during July and August – over 1200 hours servicing 62 families! This is huge for us – this shows that all our hard work has been totally worth every minute. During social respite, children were able to attend swimming, Total Ninja Warrior, Vista ridge, golf lessons, Nature Walks, visits to the playpark, and much more.

All activities were planned intentionally to meet each child’s cognitive, sensory, and social-emotional needs, and because of this, we were able to make changes as needed. We would not be able to make camp or social respite such a success without our fabulous team of staff who are able to work individually with each child to adapt activities as needed.

Thank you to everyone who helped make our summer programs and activities a big success!

|

|

|

End article-->

Daily Transition Planning and Establishing Daily Routine

Nicole Burnett

September is a month of transitions, so this got me thinking about transitional strategies and establishing routine in our daily lives. Transitions, where you move from one activity to another, are a natural part of daily life for everyone. For example, getting out of bed in the morning is a transition; so is going to school or work. Transitions can be big (like getting married) or small (like taking a lunch break); regardless of their stature, transitions can be particularly difficult for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder, causing stress and anxiety. Here are some ways that you can plan for transitions to help support someone with ASD.

First, identify problematic transitions, or ones that may potentially be challenging when establishing a new daily routine (Hume et al., 2014). For example, starting a new school routine in the mornings was particularly challenging in our household. Moving away from the slow-paced summer mornings to a structured school routine in the mornings, with more tasks, was difficult. The second step is to identify appropriate transitional strategies. The goal of a strategy is to support the individual so that they can move through a transition with less stress and anxiety, essentially making their world a little more predictable. Strategies can include, but are not limited to: priming, visual schedules, checklists, timers, and cuing (Hume et al., 2014). First, identify problematic transitions, or ones that may potentially be challenging when establishing a new daily routine (Hume et al., 2014). For example, starting a new school routine in the mornings was particularly challenging in our household. Moving away from the slow-paced summer mornings to a structured school routine in the mornings, with more tasks, was difficult. The second step is to identify appropriate transitional strategies. The goal of a strategy is to support the individual so that they can move through a transition with less stress and anxiety, essentially making their world a little more predictable. Strategies can include, but are not limited to: priming, visual schedules, checklists, timers, and cuing (Hume et al., 2014).

Priming - This transitional strategy lets the individual with ASD preview an activity so it becomes more predictable. For example, as my son transitioned into middle school this year, we took a tour of the new school before classes started. He was able to see how his classroom was set up, meet his teacher, and view examples of previous students’ projects. Priming can also include practicing a social skill before moving into the situation, or watching a video of others as they perform an activity.

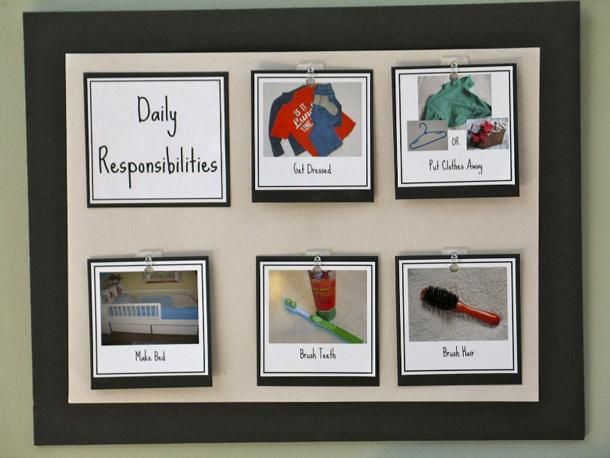

Visual Schedules - These are pictures or images sequentially displaying an activity or list of tasks so the individual knows what to expect. These are useful while establishing a new routine, and are particularly beneficial for individuals who struggle with literacy. Here is an example of a visual schedule from www.playfullearning.net

Checklists - A simple ordered list of tasks that the individual can check off once completed. We use checklists in a variety of ways. For example, a checklist can be used in place of a visual schedule for older children. Second, to break down a complex task into smaller sequential steps (e.g., doing the laundry: place dirty clothes in washer, add soap, and turn machine on).

Timers - Do you ever lose track of time when you are doing something you love? One of the reasons ASD individuals have difficulty with transitions is that they are invested in one of their perseverative interests, or do not like to transition to a new activity unless they complete the previous one.

To help with this, set a timer! The timer means it is time to move onto the next activity. If you look at my son’s iPad, he has at least 10-15 alarms set on any given day. This was something that we started to do when he had to move to online learning last year. We set timers for: when it was time to log in to the Google classroom, when lunchtime started/ended,  homework time, and to signal the end of the school day. Timers were so effective for him that we stuck with it! homework time, and to signal the end of the school day. Timers were so effective for him that we stuck with it!

Cueing - This strategy involves a simple gesture, or verbal reminder to the individual that a transition is coming up soon. A cue makes the transition more predictable and allows the individual to mentally or physically prepare for the upcoming change in activities. For example, when it is time for leave for school, I provide a 5-minute warning before we have to leave. My son will then start to put his shoes on in order to prepare, but the important point here is that he does not feel rushed to get out the door in the morning.

These are just a few examples of transitional strategies. Choose the ones that work best for you and your family. These strategies are not just useful for ASD individuals – for example, these ideas have also helped my neurotypical daughter become more independent over the years. She knows what has to be done every day, what order to do it in, and when she is done. Finally, my personal takeaway from implementing transitional strategies for our family is that I am helping my son manage his stress and anxiety, and providing him with strategies on how to make his world more predictable. I wish you all smooth transitions!

Dr. Nicole Burnett is a cognitive scientist and is currently a psychology professor at Medicine Hat College.

|

|

|

Keep on Fighting the Good Fight!

Karla Power

This summer, when I was reviewing playgrounds based on accessibility and inclusion for a project I was working on, I ran into a parent of a student I teach. When I explained to her what I was doing and how I was trying to get the municipality to build more inclusive and accessible playgrounds, she said to me, “Keep on fighting the good fight!” At the time I held on to these words as encouragement, and used them as a mantra to get through the rest of the summer. This summer, when I was reviewing playgrounds based on accessibility and inclusion for a project I was working on, I ran into a parent of a student I teach. When I explained to her what I was doing and how I was trying to get the municipality to build more inclusive and accessible playgrounds, she said to me, “Keep on fighting the good fight!” At the time I held on to these words as encouragement, and used them as a mantra to get through the rest of the summer.

You see, as much as summer is my favorite season, it is one of the most stressful ones for me, as well! While other teachers look forward to two months off from teaching, I find it sort of bittersweet. The sweet part is getting to spend time outside in the pool and go on adventures with the boys and my husband. This year we were also lucky to have grandparents visit from the East Coast.

The bitter part, or let’s call it the hard part, is that once school ends, a lot of our supports are put on hold for the summer. We no longer have the support of a CST (Classroom Support Teacher), teacher, EA, occupational therapist, physical therapist, and speech therapist from the school to help us work on our older child’s needs. Add our younger child’s needs into the mix and you’ve got two very stressed out parents who are not only trying to entertain their children for the summer, but teach them, as well!

Realizing that this would be a heavy load for us, I started advocating for funding for private speech therapy before summer began. After much fighting and many tears, we were approved for 4 hours of speech therapy for Paddy for the summer, as well as funding for a speech course that would help us work on goals for Kelton. The only problem was that this course was very intensive! Throughout the summer, I spent 2.5 hours each week participating in online group sessions, plus 3 weekly sessions of 1.5 hours each doing online video feedback with Kelton. At the end of it, I had gained some skills, but was exhausted! Realizing that this would be a heavy load for us, I started advocating for funding for private speech therapy before summer began. After much fighting and many tears, we were approved for 4 hours of speech therapy for Paddy for the summer, as well as funding for a speech course that would help us work on goals for Kelton. The only problem was that this course was very intensive! Throughout the summer, I spent 2.5 hours each week participating in online group sessions, plus 3 weekly sessions of 1.5 hours each doing online video feedback with Kelton. At the end of it, I had gained some skills, but was exhausted!

After our blur of a summer, Frank and I geared up for another school year, and began to get the boys ready, as well. School is generally a break for us, where we both get to utilize our professional skills, but we had a bit of a rocky start with school this year.

“Keep fighting the good fight” is starting to become something heavy, rather than uplifting. Don’t get me wrong: I will never stop fighting for my boys and advocating for their needs, but sometimes the fight seems relentless! I find it exhausting at times to have to fight for simple things, such as a proper playground for my children to play at, access to speech therapy for my non-verbal children, and supports and services that are not only available, but also consistent.

There is a song I love to sing from The Greatest Showman called “Never Enough”, and it speaks to my heart. Although I am grateful for everything that my boys have received, it will never be enough. I want my boys to reach for the stars, and for that they are going to need more than a step stool – they will need a very tall ladder. They will also need other people to help steady that ladder, because we will not be around forever, but that is another stressor altogether. For the rest of my days I will keep fighting the good fight, and hopefully more people will join in, and it won’t seem like such a tough battle. There is a song I love to sing from The Greatest Showman called “Never Enough”, and it speaks to my heart. Although I am grateful for everything that my boys have received, it will never be enough. I want my boys to reach for the stars, and for that they are going to need more than a step stool – they will need a very tall ladder. They will also need other people to help steady that ladder, because we will not be around forever, but that is another stressor altogether. For the rest of my days I will keep fighting the good fight, and hopefully more people will join in, and it won’t seem like such a tough battle.

|

|

|

Using Video Technology to Support Autistic Individuals

Maureen Bennie

From the Autism Awareness Centre Inc. Blog:

Video technology can be a powerful teaching tool for autistic people. The use of visual supports is a well-established and commonly used strategy with families and professionals. Using video technology for modeling takes visuals to the next level by combining the visual supports strategy with technology to create an even more effective teaching tool. Video technology is readily accessible through iPhones and iPads, easy to use, and inexpensive. It can be used with a wide range of ages, from preschool children to adults, to teach a variety of skills in a multitude of settings, such as school, home, community and the workplace. There are numerous studies to support the use of video modeling, an evidence-based intervention, with autistic individuals. Video technology can be a powerful teaching tool for autistic people. The use of visual supports is a well-established and commonly used strategy with families and professionals. Using video technology for modeling takes visuals to the next level by combining the visual supports strategy with technology to create an even more effective teaching tool. Video technology is readily accessible through iPhones and iPads, easy to use, and inexpensive. It can be used with a wide range of ages, from preschool children to adults, to teach a variety of skills in a multitude of settings, such as school, home, community and the workplace. There are numerous studies to support the use of video modeling, an evidence-based intervention, with autistic individuals.

Television-watching skills don’t need to be pre-taught, so most children will already have the necessary skills to engage in using video technology. It can be a great way to teach new skills to learners who have limited access to other means of instruction, such as print materials, or who struggle with more traditional methods of instruction. Difficulties with auditory processing often make the spoken word more challenging to understand and process, so many learners do better by watching rather than listening.

Videos can also provide predictability and give the viewer control over the speed, repetition and volume of what they’re watching. Videos take away the element of surprise that happens when interacting with people. There are no distractions or changes to deal with, so the focus can be on learning the skill rather than dealing with all of the variables humans introduce everyday. Video technology also provides built-in borders – the edges of the iPad or computer screen give a visual parameter of what to look at, unlike being in a room and not knowing where to focus attention.

Types of Video Modeling

Basic Video Modeling (BVM)

The learner watches a video of an actor other than themselves appropriately demonstrating a specific skill or routine. The actor can be a parent, sibling, peer or teacher. Prior to filming, the actor is told what to do and say during the recording process. BVM can help increase independence with daily living skills, and can increase a learner’s ability to remain calm during transitions. It can also lessen anxiety with unfamiliar situations like medical appointments or new events.

Video Self-Modeling (VSM)

VSM stars the learner demonstrating the target skill or routine. Watching a video of oneself performing a skill or task correctly is reinforcing and builds confidence. Psychologist Albert Bandura found that the most effective models are those that are most similar to the individual. Whenever possible, film the individual, but if you can’t, then use a model that is similar to the learner. Research shows that watching oneself on a video can increase the person’s ability to attend to the video. Another benefit is the “movie star” effect – many children increase their ability to demonstrate a skill just because they know they are being filmed. My son is like that! VSM stars the learner demonstrating the target skill or routine. Watching a video of oneself performing a skill or task correctly is reinforcing and builds confidence. Psychologist Albert Bandura found that the most effective models are those that are most similar to the individual. Whenever possible, film the individual, but if you can’t, then use a model that is similar to the learner. Research shows that watching oneself on a video can increase the person’s ability to attend to the video. Another benefit is the “movie star” effect – many children increase their ability to demonstrate a skill just because they know they are being filmed. My son is like that!

Feedforward is another type of VSM where the learner sees himself demonstrating a skill that is slightly beyond his current capabilities. This type of video can be used if the learner:

a) can only demonstrate some, but not all, of the behaviors needed to perform the target skill

b) is only able to perform the skill at a low level of mastery

c) needs support to demonstrate the behaviours required to perform the skill

Point-of-View Modeling (PVM)

This is similar to Basic Video Modeling in that you are recording a person other than the learner, but the recording captures exactly what the learner will see through their own eyes while demonstrating the skill or routine. Because the video shows the skill from the learner’s point of view, the video only includes the model’s hands, as well as any social partners that are necessary for the skill to be demonstrated.

PVM videos are an effective way to teach any new skill that the learner can’t demonstrate yet without a substantial amount of support from another person, because the learner isn’t the one performing the skill in the recording.

My two adult children access YouTube videos frequently, which provides the user point-of-view, when they are going to a new place or activity. For example, my son watched every ride for Disneyland ahead of time so he would know what to expect when he got there, and what the ride looked like once you were on it in motion.

The 10 Steps for Video Modeling

- Identify the skill or routine you would like to target.

- Identify and assemble the materials needed.

- Do a task analysis of the skill or routine and collect baseline data. (In other words, break the skill down into steps and observe each step.)

Make a plan for the filming of the video (including the type of modeling, language used, and who will film). Make a plan for the filming of the video (including the type of modeling, language used, and who will film).- Record the video.

- Edit the video footage, if you need to.

- Show the video to the person.

- Facilitate skill development after viewing the video. (Continue support with visuals and nonverbal prompts.)

- Monitor the person’s progress to see if changes need to be made.

- Problem solve if progress is too slow. (Are you showing the video often enough? Is it too long? Is it the wrong type of video modeling? Does the skill have too many steps that are beyond the person’s reach?)

There are many areas where video modeling can be used, such as communication, teaching voice volume, identifying emotions, how to self-regulate through breathing, using a locker, crossing the street, job interview skills – the list is endless. The good news is there is lots of support on how to do video modeling successfully – for example, check out YouTube, or take a look at the books in the references below.

References

McGinnity, K., Hammer, S., Ladson, L. 2011. Lights! Camera! Autism! Using Video Technology to Enhance Lives. Wisconsin: Cambridge Review Press

Murray, S., Noland B. 2013. Video Modeling for Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. London: Jessica Kingsley Press

|

|

|

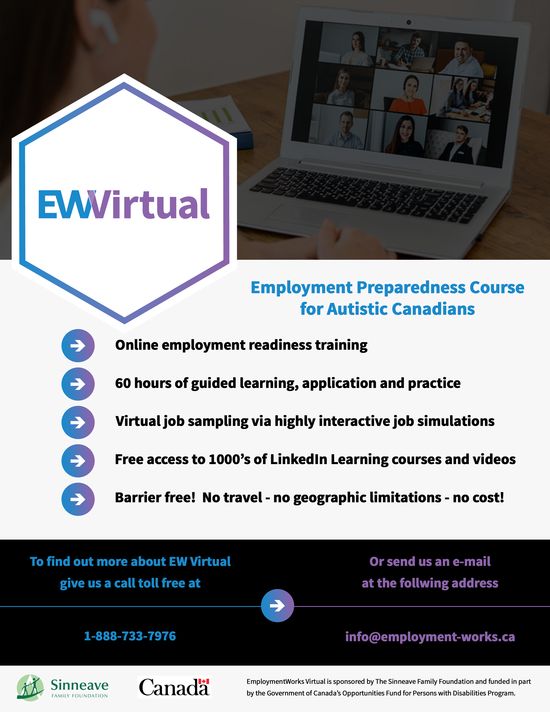

EmploymentWorks Virtual

Click the poster below to see a larger version

|

|

|

End article-->

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

Autism Society Alberta will be closed September 30th in recognition of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. As an organization we commit to recognizing the truths and stories of residential school survivors, and as we move forward have taken steps to learn and listen to Autistic Indigenous individuals and their families.

Autism Society Alberta will be closed September 30th in recognition of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. As an organization we commit to recognizing the truths and stories of residential school survivors, and as we move forward have taken steps to learn and listen to Autistic Indigenous individuals and their families.

Resources

Orange Shirts

Residential School Survivor Donations

Truth and Reconciliation

|

|

|

End article--> |

|